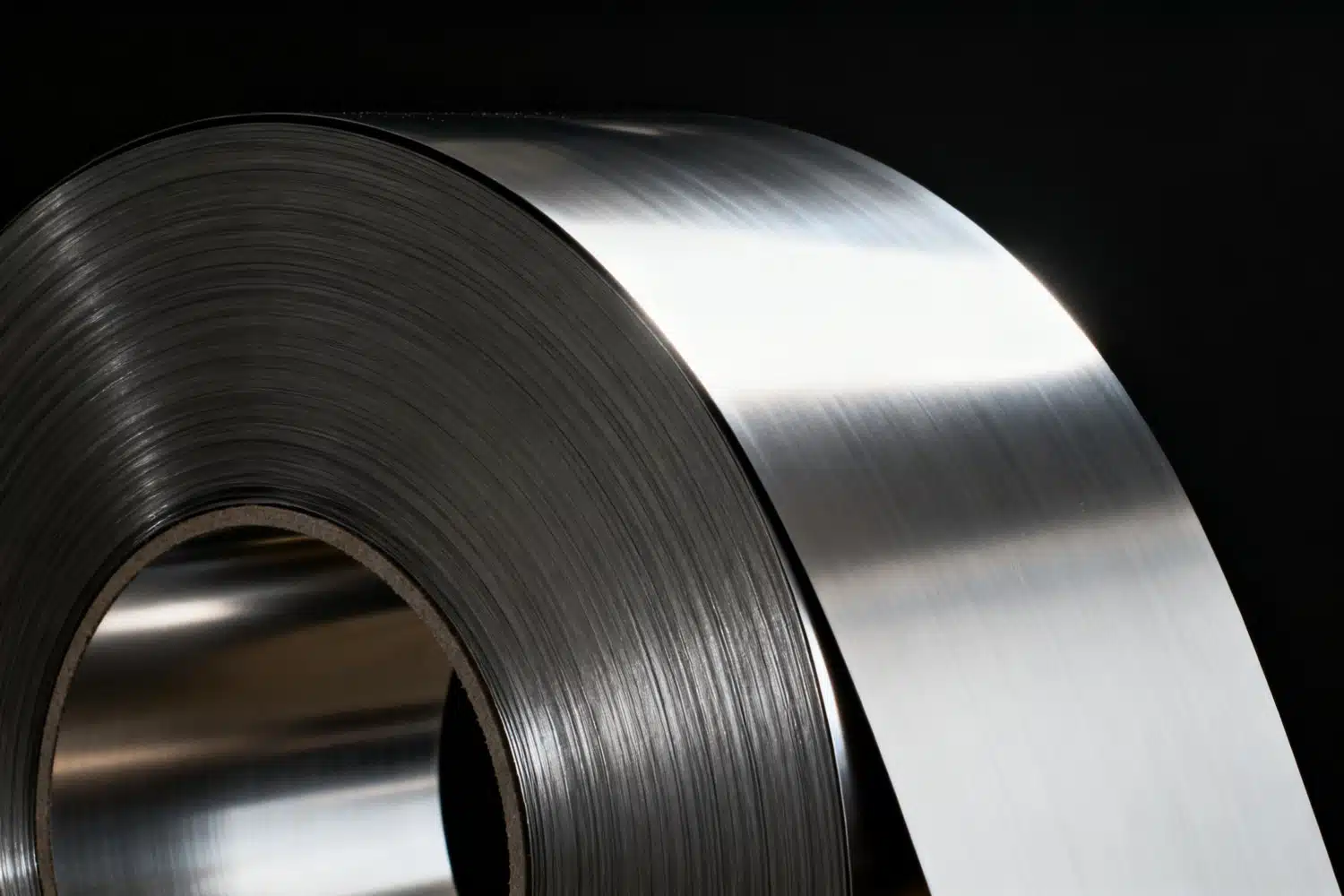

Stainless steel’s versatility stems not only from its alloy composition but also from its mechanical processing states. Among cold-worked stainless steels, Half Hard (1/2H)and Full Hard (FH)represent two critical points on the strength-ductility spectrum. While both are produced through cold reduction, their divergent properties dictate vastly different engineering applications. Understanding these differences is essential for material selection in precision manufacturing, aerospace, automotive, and industrial tooling.

1. Metallurgical Foundations: How Cold Work Defines Hardness

Cold rolling—the primary process for achieving these tempers—induces permanent microstructural changes:

- Dislocation Density: Plastic deformation multiplies lattice defects, impeding dislocation motion and raising strength.

- Martensite Formation: In metastable grades (e.g., 301), strain-induced austenite transforms to martensite, amplifying hardness.

Half Hard (1/2H) undergoes 20–25% cold reduction, balancing dislocation hardening with retained ductility

Full Hard (FH) experiences ≥50% reduction, nearing dislocation saturation and maximizing strength at the cost of formability.

2. Mechanical Properties: The Core Divergence

Property | Half Hard (1/2H) | Full Hard (FH) |

|---|---|---|

Tensile Strength | 860–1,000 MPa | 1,130–1,300 MPa |

Yield Strength | 550–690 MPa | ≥880 MPa |

Elongation | ≥15% | ≤1% |

Hardness (HV) | 300–350 | 370–430 |

Fatigue Strength | ~400 MPa | ~650 MPa |

Key Implications:

Strength vs. Ductility Trade-off:

- 1/2H: Retains 15% elongation, permitting bending radii down to 4× material thickness (e.g., automotive trim, brackets).

- FH: Minimal elongation (≤1%) makes it unfit for post-roll forming; any bending risks fracture.

Fatigue Behavior:

- 1/2H: Moderate cyclic load capacity suits dynamic applications (e.g., conveyor parts).

- FH: Higher fatigue strength (~650 MPa) benefits static, high-stress components (e.g., industrial blades)

3. Processing and Fabrication Challenges

3.1 Cold Reduction Techniques

- 1/2H: Achieved via tandem rolling mills with emulsion cooling to limit temperature rise (<150°C), preserving microstructure.

- FH: Requires multi-pass rolling (≥50% reduction) with precise thickness control (±0.005 mm).

3.2 Forming Limitations

Operation | Half Hard (1/2H) | Full Hard (FH) |

|---|---|---|

Bending | Radius ≥4× thickness | Avoid entirely |

Stamping | Shallow draws (≤1.5× thickness) | Only flat parts; no forming |

Welding | TIG/laser with low heat input | Risk of HAZ cracking; avoid |

Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC): Both tempers accumulate residual stresses, but FH is 3× more susceptible to chloride-induced SCC. Mitigation requires stress-relief annealing (300–400°C) for FH parts in corrosive environments.

4. Application Domains: Where Each Temper Excels

Half Hard (1/2H) Applications

- Automotive: Wheel covers, trim moldings (balance of dent resistance and formability).

- Architecture: Handrails, facade supports (structural rigidity + aesthetic shaping).

- Conveyor Systems: Guide rails, flight bars (fatigue resistance + moderate wear hardness).

Full Hard (FH) Applications

- Industrial Tools: Cutting blades, shims (maximized abrasion resistance).

- Springs & Fasteners: Lock components, springs (high yield strength for elastic recovery).

- Ballistic/Defense: Fragmentation panels (hardness defeats penetration).

5. Cost and Lifecycle Considerations

- Production Cost: FH requires 2–3× more rolling passes than 1/2H, increasing energy and tooling expenses.

- Failure Risks: FH’s brittleness raises fracture risk in dynamic loads; 1/2H offers better impact tolerance.

- Corrosion Maintenance: FH demands protective coatings or annealing in harsh environments, adding lifecycle costs.

6. Material Selection Guidelines

Choose Half Hard (1/2H) when:

- Moderate forming (bending, shallow drawing) is required post-rolling.

- The component faces dynamic loads (e.g., brackets, trim).

- Cost-effective fabrication without annealing is critical.

Choose Full Hard (FH) when:

- Absolute maximum hardness and wear resistance are non-negotiable (e.g., blades).

- The part geometry is simple and flat (no bending or welding needed).

- The environment is controlled (low humidity/chlorides) or stress-relieved.

Conclusion: Balancing Strength with Practicality

The choice between Half Hard and Full Hard stainless steel hinges on fundamental trade-offs:

- 1/2H occupies the sweet spot for functional versatility, offering substantial strength gains (2–3× annealed yield strength) while retaining manufacturability for bending and stamping.

- FH delivers unmatched hardness and rigidity but sacrifices all post-roll formability, restricting it to flat, static, or minimally corrosive applications.

For engineers, success lies in aligning temper selection with fabrication constraints, operational stresses, and environmental exposure. Specifying 1/2H for structural components or FH for wear-critical tools ensures optimal performance while mitigating the risks of premature failure—a decision that ultimately defines product lifespan and safety.